|

||||||||

|

California

October conference postponed until next year

Congratulations to Chicago Botanic Garden

map of the three islands of Sansho-en (Elizabeth Hubert Malott Garden) courtesy of Chicago Botanic Garden

The United States Postal Service announced a set of 10 gardens to be issued on stamps in 2020.

Among the selection is the Elizabeth Hubert Malott Japanese garden at Chicago Botanic Garden, the second time a U.S. Japanese garden has appeared on a stamp.

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/gardens/japanese

The first U.S. garden on a stamp was Lili`uokalani Gardens in Hilo on a Priority Mail stamp in 2017, marking the centennial of Hilo’s treasured cultural landscape.

Issued to mark the centennial of Lili`uokalani Gardens, this also is the first time a Hilo locale appears on a U.S. postage stamp and the first time a Japanese garden appears on a U.S. postage stamp

Other gardens in the new Forever stamp set that also have Japanese gardens within their boundaries are Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens (Ohio), Huntington Botanical Gardens (California), and Brooklyn Botanic Garden (New York).

Training Opportunity in San Francisco

The North American Japanese Garden Association will hold a spring regional event at the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco in April.

“The Past Becomes Present: A Design Workshop” will be held Friday and Saturday, April 5 and 6. Advance registration is necessary.

Please go to the NAJGA web site for more information and to register.

North American Japanese Garden Association plans regional conferences in 2017

Descanso Gardens in Flintridge near Los Angeles will host the North American Japanese Garden Association regional conference in January 2017 Photo courtesy of Descanso Gardens

California and Texas will play host to regional conferences of the North American Japanese Garden Association in January and February 2017.

Saturday and Sunday, January 14 and 15, 2017 a regional conference will be held in Southern California at Descanso Gardens in Flintridge.

Marking the 50th anniversary of Descanso Gardens, the conference is designed to “explore the Japanese garden experience in Southern California in a two-day regional event featuring hands-on workshops, an exhibition, lectures on horticulture and history and expert-led tours of five Asian gardens,” said a release from the North American Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA).

“Descanso Gardens, just northeast of downtown Los Angeles, is celebrating the 50th year of its Japanese garden. Descanso is embracing the garden’s evolving form, its identity as a focal point for a multi-cultural community and its role in inspiring new artistic creation. For lovers of camellia, a familiar plant in the Japanese garden, Descanso is home to the largest camellia collection in North America.

“The Japanese garden at the nearby Huntington boasts a history over 100 years as well as a legacy of evolution and renovation seen in its restored Japanese House and a new tea garden. Two other large gardens in the area — the SuiHoen (Garden of Water and Fragrance) in Van Nuys and the Storrier-Stearns Japanese Garden in Pasadena — illustrate how Japanese gardens can demonstrate the sustainable use of water in even an arid climate. All of these gardens feature exceptional garden architecture that makes use of Southern California’s year-round warmth and indoor-outdoor lifestyle.”

For further information and to register, contact NAJGA at http://www.najga.org/Southern-California-2017

In February — 10 through 12, the Japanese Garden at Fort Worth Botanical Garden and the Meiners garden in Grand Prairie will host a NAJGA regional conference.

The following text is quoted from the NAJGA web site offering registration for Texas events.

“The diverse topography of the state of Texas contains elements associated with both the southern and southwestern parts of the United States, from the rolling prairies, grasslands, forests and coastlines in the east to the deserts of the southwest. As big as the land itself is the canvas of myriad possibilities for expressing the landscape-inspired artistry of a Japanese garden in the Lone Star State.

“The Japanese garden at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden and a private garden located in the city of Grand Prairie illustrate the range of traditional and contemporary landscape artistry worked into that sprawling canvas. The 7.5-acre garden in Fort Worth incorporates both a traditional stroll garden with a water feature and two interpretations of the dry landscape style. The Meiners Garden in Grand Prairie is an example of the adaptability of the Japanese garden aesthetic, with its emphasis on responding to the environment in which the garden exists. The tea garden and the hill-and-pond garden are seamlessly integrated with the residence in traditional Japanese manner. A larger pond garden in the premises is a parallel ongoing project.

“These gardens illustrate how Japanese gardens are always a work in progress. On February 10, 11 and 12, the North American Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA) offers a rare opportunity for participants to both shape the future of these gardens and appreciate them through hands-on sessions. The sessions include the repair and maintenance of man-made and horticultural elements, the creation of a new water feature, and a day of learning with a focus on the tea garden tradition.

“This regional event is highly recommended for landscape and horticulture professionals in the south and southwestern US with an interest in Japanese garden design, construction and maintenance. For garden owners and other enthusiasts, the event provides an instructive inside view of two gardens in evolution that can relate to their own creation / maintenance concerns and garden study.”

Activities included in the workshops include: bamboo fence repair, shaping of wave-form foliage, preparing trees for transplant, head water and stream construction, tours and tea ceremony.

This event is eligible for CEUs (continuing education units) with professional organizations. See the NAJGA web site and registration form for more information.

Balboa Park planned for years to celebrate centennial

impressive entry sign on the corner across from the Spreckles Organ; the cafe straight ahead provides monthly income; the entry gate is to the right of the cafe [Bill F. Eger photo]

red ribbon marks size of original Japanese garden; model shows size of expansion completed in time for centennial

San Diego’s civic leaders set aside 1,400 acres in 1868 for a park. It sat unused for more than 20 years until Kate Sessions stepped forward with an offer to plant 100 trees a year in the park as well as donations to other sites in San Diego. An exchange was worked out for 32 acres within the park for her commercial nursery.

After the turn of the century, a master plan was introduced, taxes levied, and a water system installed. In 1910, planning was underway for the first World’s Fair to be held on its grounds and, after months of discussion, Park Commissioners decided on renaming City Park as Balboa Park.

The Panama-California Exposition of 1915-1916 marked the first Japanese tea house within park boundaries at a different location than the present cafe.

The Japanese Friendship Garden of San Diego began in 1990 with a dry garden and pavilion by Ken Nakajima on about an acre and a half site between the Spreckles Organ and the Hospitality House. In 1999 a cafe and patio were added to generate revenue for the garden and a koi pond was installed.

In 2010, ground was broken for garden expansion to nearly 11 acres including an adjacent canyon. Designed by Takeo Uesugi and Associates, the expanded garden includes huge rock waterfalls, meandering paths, traditional bridges, a culture center and cherry tree grove. Tea houses remain to be constructed.To plan a trip to the Japanese Friendship Garden of San Diego or see the events calendar, please review the web site: http://www.niwa.org/

For additional information on all of Balboa Park, please contact the web site: http://www.balboapark.org/

or for the app, text Balboa Park to 56512.

We welcome thoughtful remarks and questions. Do not waste your time trying to post spam as all comments are reviewed before publishing.

Any otherwise uncredited photos are by K.T. Cannon-Eger. Please feel free to share this blog and please be nice and give credit when you do.

Short walk in Los Angeles yields several gardens

Los Angeles, San Jose, and San Francisco plus a few places remaining in Berkeley and San Diego offer visitors to those California cities glimpses into the old days of Japantowns. Here a daruma is one image of three on fans attached to utility poles throughout Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. [photo by K.T. Cannon-Eger]

As is true with many gardens, it is named not for the location, organization, or designer. This is the James Irvine Japanese Garden named for the foundation whose generosity made this hidden gem possible. It also is known as Senryu-en, Garden of the Clear Stream.

David Sipos hand planed and traditionally built bridge is holding up very nicely

For more information on the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center, please look at their web site: http://www.jaccc.org/#japanese-american-cultural-community-center

Across the brick plaza and past the Isamu Noguchi sculpture to the other side is a wonderful wander through the stores and restaurants of Little Tokyo.

On the other side of that is East First Street and the “new” Nishi Hongwanji of Los Angeles.

Members of the sangha took time to point out how grateful they felt to have quite a number of landscapers among their membership. My personal favorites were the rustic lantern on the First Street side and several beautifully pruned pines.

For more information on the Nishi Hongwanji Los Angeles Betsuin contact their web site: http://www.nishihongwanji-la.org/

Back up First Street is the old Nishi Hongwanji building, now part of the Japanese American National Museum campus.

Exterior glass admits great light far into the interior. The glass is continued inside with a very subtle gratitude to donors “wall” between the great hall and the outdoor cafe.

For more information on the Japanese American National Museum, contact their web site: http://www.janm.org/

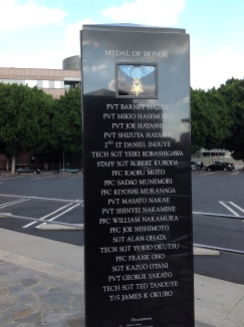

Between the old Nishi Hongwanji and the Japanese American National Museum, a wide plaza leads back to monuments dedicated to Japanese American service in World War II. “Go For Broke” was their motto.

Further up the street is Anzen Hardware, covered in an earlier post.

https://us-japanesegardens.com/2013/10/19/where-do-i-find/

And then back to the hotel we chose for proximity to all these places and the exquisite third floor garden, accessible via elevator from the lobby.

Kyoto Gardens has become a Hilton DoubleTree. The garden hosts many wedding parties.

Before leaving town the following morning, we walked down the street to see the Higashi Hongwanji gardens, presently being maintained by the son of one of the garden’s builders.

Please do not waste your time trying to post unrelated material (spam). All comments are reviewed before they appear.

Photos by K.T. Cannon-Eger. We welcome helpful remarks and sharing of material. If you share, please be nice and give credit.

Long time favorite still pleases

In the early 1970s, my husband and I lived in San Francisco before moving to Hawaii. We used to walk all over the city, sometimes hopping on a bus, streetcar or cable car.

Golden Gate Park was a favorite for exhibits at the DeYoung, competitions at the Hall of Flowers, and peaceful respite with tea at the Japanese garden. Coming back to the city in 2012 was a wonderful time to visit with much missed friends. We enjoyed a progressive dinner in Little Italy with appetizers, main course, and coffee with dessert in three different places.

And we couldn’t wait to see the new (to us) additions to the San Francisco Japanese Tea Garden.

The South Gare, originally from the Japan exhibit at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, was partially rebuilt in the 1980s [photo by Bill F. Eger]

“When the fair closed, Japanese landscape architect Makoto Hagiwara and [park] superintendent John McLaren reached a gentleman’s agreement, allowing Mr. Hagiwara to create and maintain a permanent Japanese style garden as a gift for posterity.”

The Californi fair came to be because Michael H. deYoung was a Presidential appointee to the 1893 fair in Chicago — the World’s Columbian Exposition — and he saw the benefits to his home state. Soon, plans were underway to hold a six-month exhibition in Golden Gate Park from late January to early July 1894.

The San Francisco Japanese Tea Garden is the only ethnological display still in existence from that fair. And Makoto Hagiwara poured his talents and personal wealth into expanding its gardens to five acres.

real ducks mingle with metal cranes in a pond [photo by Bill F. Eger]

waterfall, stones and lantern reflect in a pond below the iconic tea house [photo by Bill F. Eger]

The street in front of the garden entry was renamed Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive and in 1974 artist Ruth Asawa donated a plaque honoring the Hagiwara family’s dedication.

seasonal color comes with summer’s iris [photo by K.T. Cannon-Eger]

traditional pathways blend with more modern walkways [photo by K.T. Cannon-Eger]

For more on the history of the San Francisco Japanese Tea Garden, please refer to the garden’s web site mentioned above, and to the web site of Eric Sumiharu Hagiwara-Nagata http://www.hanascape.com/

All comments are reviewed before publishing. Please do not waste your time trying to post spam in the comments.

Should you like this article and wish to share, please be nice and give credit.

Mahalo.

Private gardens add to general knowledge

One of the benefits of doing what we love and telling people about our travels is the occasional invitation to a private garden. Some are residential, some corporate, but they share the characteristic of being unavailable to the general public except for special occasions such as a group garden tour or other by-invitation-only event.

Such was the case with a residential garden and a corporate roof top garden, both in northern California.

a view from the kitchen continues unobstructed to a hillside waterfall, making great use of the natural terrain photo by Bill F. Eger

The big lesson from this garden, once again, is the joy attained by inviting the outside in and extending the inside out. Every piece of furniture was arranged to take advantage of the view. No sofa was placed blocking a window. Distant views were “borrowed” to make the garden seem much larger.

The residential garden was in hilly country. Crossing a bridge into a busy urban area, we were invited to a roof top garden constructed decades ago. Within the past ten years, the trees and stones were lifted, repairs made, and all replaced to return serenity to the area.

redone due to engineering concerns, the Japanese roof top garden offers serene views to corporate executives photo by Bill F. Eger

a pathway runs between plantings to a lantern arrangement with coin basin nearby Photo by Bill F. Eger

placement of this coin basin brought to mind another basin in a different state, visible in the next photograph

Consulting friends in the business, this catalog photo from Kyoto confirmed the correct placement

This is one small way in which visiting one garden can assist another, even if it is a small thing like advising the southern garden to turn their basin around.

We welcome comments to this blog’s articles. Please do not waste your time trying to post spam. All comments are reviewed before publishing. Be nice.

Photos not otherwise credited are by K.T. Cannon-Eger. Should you choose to re-post a blog entry or use a photo, be nice and give credit. Mahalo and arigato.

Stones at UC-Berkeley Japanese pond date back to 1939 World’s Fair on Treasure Island

Placement of the stones in the Japanese garden at the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island was designed by Kaneji Domoto, who later oversaw moving the stones to UC Berkeley for the Japanese pond in the botanic garden.

(Photo reproduced courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, donated by Francis and Gloria Massimo) The Exposition was held in 1939, the same year Domoto worked on another garden in New York for an exposition there.

[the following quoted information on Kaneji Domoto is excerpted from the Taliesin Fellows newsletter #12 July 15, 2003]

Kaneji (known as Kan) Domoto was born on November 5, 1913 in Oakland California, the eighth of eleven children. At the family nursery in Hayward, he learned to propagate camellias and peonies for which his nurseryman father had become famous.

“Domoto attended Stanford University studying science and physics, and played on the soccer team. He also studied landscape architecture at the University of California in Berkeley.

“He apprenticed at Taliesin in 1939 and began his career as architect and landscape architect in California. He came east to assist in the creation of the Japanese exhibit for the New York World’s Fair following work for the San Francisco Treasure Island Fair.”

With the advent of World War II, Domoto was interned with his wife, Sally Fujii, at Granada War Relocation Center [also known as Camp Amache] Colorado. At the end of the war, they moved to New Rochelle, NY with their children, Mikiko and Anyo. Later two more children, Katherine and Kristine, were born in New Rochelle, NY, where he made his home for many years. Domoto died January 27, 2002.

“Domoto had a long and productive career in architecture and landscape design. He designed several homes at the famous Frank Lloyd Wright Usonia homes development at Pleasantville, NY. He designed landscapes for residential and commercial projects, mainly in Westchester County but also in surrounding northeastern states. He became noted for his use of huge stones and rocks in his well-known Japanese-American gardens at the New York World’s Fair Japanese Exhibit, in Berkeley, California, Jackson Park, Chicago, and Columbus, Ohio.

“His career produced more than 700 projects, and Domoto received many awards for his work, including the Frederick Law Olmsted Award for his Jackson Park design. He donated many hours to local and national civic associations throughout his career.

“His wife, Sally, died in 1978, and his second wife, Sylvia Schur, survives him [at the time this was written in 2003]. He leaves 4 children, 6 grandchildren and 1 great granddaughter, 2 sisters, and a number of nieces and nephews.”

The Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island celebrated the opening of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay (Bay Bridge) Bridge in 1936, as well as the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937.

Domoto also published a book on bonsai. His brother Toichi Domoto remained in California with the nursery business and is featured in oral histories in the UC-Berkeley collection on the growth of the California landscape industry.

The area of the Japanese pond in the botanic garden on campus is known as Strawberry Creek. According to director Paul Licht, the area was a dairy before becoming a pond.

Work on the Japanese garden began in November 1941. Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the stones and lantern were moved to a warehouse for safekeeping and the garden was not completed until after the war ended.

Elaine Sedlack shows the donated gate at the UC-Berkeley pathway to the Japanese pond. Sedlack laid the pathway stones that go through the gate built by Paul Biscoe. Retaining wall stone masonry was by Shigeru Namba.

Curator Elaine Sedlack has gardened since 1969 and has been with the Asian collection since 1984. She is active in international plant societies including maples and rhododendrons. Sedlack noted that a flood in 1965 brought a lot of mud down the slope and that the lantern was damaged at that time.

Over the years, many improvements and additions have been made. Shigeru Namba, a stone mason from Osaka living in California, built retaining walls around the gate built by woodworker Paul Biscoe. Namba, his wife Sakiko and their two year old daughter drove in from Woodside to set a lantern obtained in Japan by landscape architect Ron Herman.

The gate and the lantern honor the involvement of two stalwarts of Berkeley’s Japanese-American community: artist Chiura Obata and ikebana teacher Haruko Obata, his wife.

The lantern is dedicated to Haruko Obata for her contributions to the art of flower arranging. As early as the 1915 exposition in San Francisco, her work was important enough to warrant an entire room for display.

“To my thinking there is no great art without Nature.” Chiura Obata (1885-1975)

Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was born in Japan and came to California in 1903. A master in the traditional Japanese sumi ink and brush technique, he also excelled in art education and taught at the University of California, Berkeley from 1932 until 1954, except for the years of internment. Many works were published in the book Obata’s Yosemite (Yosemite Association, 1993).

In 1932, Obata began his teaching career at the University of California. For watercolor painting, he gave his students the traditional Japanese materials: the brush, ink of pine soot, colors from vegetable and mineral pigments, and silk and paper as media. In 1938, Time magazine called Obata “one of the most accomplished artists in the West.” Known for defining the nihonga style of painting—a technique that blends Japanese traditional ink painting with Western methods—Obata influenced a generation of artists who were part of the California Watercolor Movement in the 1920s and ’30s.

His popular classes were interrupted by evacuation first to Tanforan and then to Topaz internment camp in Utah in 1942. Even under these conditions, Obata painted prolifically and organized art schools in the camps with as many as 650 students from the internees.

His granddaughter Kimi Kodani Hill notes, “His experience of knowing nature consoled and inspired him,” Hill says. “He always told his students at the camp ‘don’t just look at the dust on the ground, look beyond.’” Hill is editor of Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment, with an introduction by Timothy Anglin Burgard and foreword by Ruth Asawa.

Smithsonian exhibit, A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution: “All the families did some gardening about their dwellings in order to beautify them. Everything had to be brought in from the mountains, rocks, trees and shrubs.” Chiura Obata about the garden outside the family quarters at Topaz; illustration used with permission from the family.

He returned to the University of California in 1945 and resumed his faculty position. Former University President Gordon Sproul and several students had kept many artworks safe during the war and returned them to Obata. He traveled extensively as he lectured, sketched, painted, and gave one-man exhibitions at major galleries and museums.

In 1965, Obata received the Kungoto Zuihosho Medal, an Imperial honor and accolade, for promoting goodwill and understanding between the United States and Japan.

From 1954 to 1972 Obata was a tour director, taking Americans on regular visits to renowned gardens, temples, and art treasures in Japan. Students continued to gather at his Berkeley home on Ellsworth Avenue to study painting.

Their studio on Telegraph Avenue was voted a landmark in 2009 by the Berkeley Landmarks Preservation Commission.

“As most of us in California know, the need for uncovering Japanese-American history—the reason it is hidden in our communities—is that the U.S. government made a heinous error in the anxious time at the onset of World War II,” social historian Donna Graves told The Berkeley Daily Planet. Graves nominated the Obata Studio for landmark status, “Federal policy dictated that people of Japanese descent, whether they were American citizens or not, were forced to leave their communities, homes, and businesses in the spring of 1942 and incarcerated in remote concentration camps behind barbed wire and under armed guard. This act, which was not perpetrated on people of German or Italian descent, irreparably harmed communities that Japanese-Americans had built in cities like Berkeley and across California. This is a story we Americans must remember, and it is part of what inspired the landmark application.”

Graves heads Preserving California’s Japantowns, a statewide survey of pre-World War II Japanese-American historic resources. Funded by the California State Libraries, the project has identified hundreds of locations in nearly 50 cities from San Diego to Marysville.

For more information on the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, to plan a visit there, or to find out about classes and plant sales, visit the web site http://botanicalgarden.berkeley.edu/

To see any photo in this article full size, click on the image. Unless otherwise noted in captions, photos are by K.T. Cannon-Eger. Please be nice and do not copy without permission and attribution.

Comments are welcome. All comments will be read and approved before they appear.

Where do I find…..

The right tool makes any job easier. Finding the right tool can be something of a pilgrimage.

We are fortunate in Hilo to have Garden Exchange close at hand for bamboo splitters, hand forged pruners, and properly balanced hedge shears.

For those seeking carpentry tools as well as garden supplies, sewing kits, and bonsai equipment there are several wonderful places we visited on the mainland.

Friends in Phoenix, Arizona tipped us to Anzen Hardware in Los Angeles.

Located on East First Street near the Japanese Village Plaza Mall, Anzen Hardware is full to the rafters with wonderful goods. Chefs seek this store out for its fine selection of quality knives. Sake makers come here for their supplies. There are bamboo brooms and gravel rakes for the gardener.

Fans call it an old fashioned hardware store for the handyman. Best of all is owner Nori Takitani who started as a high school part time worker in 1954. One of the elders of the community, he can be counted on for good service and advice.

My favorite purchase from this store (so far) were the vegetable seed packets along with good advice from Nori to put them in the refrigerator first “to wake them up” before planting.

Another seed source was the gift shop at the Japanese American National Museum a few blocks down the street. Kitazawa Seed packets and a well stocked bookcase were favorite attractions in the JANM store.

Contact the museum at: http://www.janm.org/

Or find Kitazawa Seed at: http://www.kitazawaseed.com/

To the north is Hida Tool on San Pablo Avenue in Berkeley.

Like Anzen, Hida Tool has crowded shelves, knowledgeable staff, and museum pieces on the wall. In addition to the store, Hida Tool has gone high tech with a web site.

As mentioned on their site, “Hida Tool was started in response to requests from San Francisco Bay Area woodworkers to get tools like those being used by Makoto Imai, who had come from Japan in 1978 after his 5-year apprenticeship in carpentry plus 9 years as a teahouse and temple builder. His were the hand tools of the builders of traditional homes and temples in Japan, including saws with both crosscut and rip teeth on the same blade, planes with wooden bodies quite different from those of European and early American wooden planes, and both plane blades and chisels forged by methods developed by the blacksmiths who created the famous samurai swords. These tools had a layer of very hard steel forged to a larger mass of softer iron, which allowed the formation in the tempering step of a harder cutting edge than was permissible in tools made entirely of similar carbon steel.

Wandering down the street from our hotel in San Francisco, we came upon Soko Hardware on Post Street. Another family-style hardware store carrying excellent culinary knives, garden supplies, woodworking tools, plus kitchen equipment, fine dishes, paper lanterns, and seeds among many other items.

Owned and operated by the Ashizawa family since 1925, Soko Hardware is now under the guidance of the third generation, Roy Ashizawa.

http://sfjapantown.org/soko-hardware/

A Yahoo reviewer noted of Soko Hardware: “The ceramics section holds a dizzying array of vases in aesthetic organic shapes, plates in all sizes and shapes, and platters suitable for a tea ceremony. Traditional finishes, such as oxblood and crackle glaze are the order of the day and the quality of everything is good whatever the price tag.”

Garden and museum gift shops are another source.

Heritage seeds from the time of Thomas Jefferson can be found in the gift shop at Monticello.

“…there is not a sprig of grass that shoots uninteresting to me…” Thomas Jefferson said in a 1790 letter to his daughter.

Bamboo fabric gloves were a favorite purchase from the Chicago Botanic Garden gift shop.

Organic products of all kinds, including seeds, were available at Weatherford Gardens just outside of Fort Worth, Texas.

http://www.weatherfordgardens.com/

Where do you go to find that special thing for your garden? Comments are welcome.

Be nice! All photographs appearing in this blog are the property of K.T. Cannon-Eger or Bill F. Eger. All the photography on this blog is protected by U.S. Copyright Laws, and are not to be manipulated, downloaded or reproduced any way and may not be used in commercial or political materials, advertisements, emails, products, promotions without written permission. Copyright 2013 K.T. Cannon-Eger All Rights Reserved.