[NOTE: The following article was prepared in mid-2012. Since that time, this garden has a new name: “The Garden of the Phoenix.” To learn more about activities planned for the 120th anniversary celebration March 31, 2013 please go to the garden friends’ group’s web site: http://gardenofthephoenix.org/ ]

From the first “Great Exposition” of 1851 in London, more than 90 world’s fairs have been held — most of them in Europe, the United States, Canada and Japan.

Though the themes may have differed, the motives were strikingly similar: “to commemorate a historic event, to educate and entertain, to sell new products, to peer into the future, and, although it’s rare, to turn a profit for the sponsors,” as noted by Norman Bolotin and Christine Laing in their 2002 book The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 published by University of Illinois Press.

To this day, we can enjoy remnants of those fairs: The Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco dates back to an 1854 fair; the Japanese Friendship Garden in San Diego at Balboa Park dates from a tea pavilion at a 1915 fair. The present Osaka Garden had its beginning as Wooded Island in the 1893 World’s Columbia Exposition with additions following the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: A Century of Progress.

In looking at all the world’s fairs, Bolotin and Laing noted: “when it comes to pure scope, grandeur and far-reaching legacies, the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 outshines them all. Twenty-eight million visitors (in six months). Buildings stretching a third of a mile long. The world’s first Ferris Wheel — with cars the size of buses! The first amusement section ever at a fair. Replicas of a full-size battleship and Columbus’ three caravels. Architectural impact reaching into the new century.”

Looking southeast from the Illinois Building on the 1893 fair grounds, a bridge led to Wooded Island, a peaceful retreat for fairgoers amid 200 buildings constructed for the six-month fair. The present Osaka Garden site is in the wooded area to the left of the Ho-o-den buildings.

photo from The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, the White City Artfolio

Wooded Island was at the center and provided respite from the bustle of the fair. On the north end, three buildings were constructed representing Japanese architecture from the 12th, 16th and 18th centuries. They were connected to form the shape of Ho-o, a mythical bird like the phoenix. Some suggest the phoenix was used as an emblem for the City of Chicago, reborn from the great fire of 1871.

To get an idea of where this park is located, take a look at Google maps:

The red pin marks an approximate location for Osaka Garden on Wooded Island in Jackson Park on the south side of the Museum of Science and Industry. It is easily reached by bus or car.

(Google Maps)

In a history for the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference Parks Committee, Gary Ossewaarde wrote:

“The 1893 Ho-o-Den consisted of three structures joined by covered walkway to form the shape of the phoenix bird, which it did resemble from ground level). The beams and joinery were part of the beauty and ornament. Inside were artifacts and treasures from three periods of Japanese history-scrolls, vases, decorative screens, writing materials, and musical instruments. A major feature was the lanterns– both the elaborate stone ones and the paper lanterns at ceiling level. The elements and art were designed and crafted in Japan and brought over by steamer and train, along with carpenters, stone workers and gardeners. The construction itself was an activity that drew many visitors. A reporter wrote, ‘They move about serenely as if it were a pleasure to work’.

Another view of the Ho-o-den on Wooded Island at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

(Dream City: A Portfolio of Photographic Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition)

“The Japanese exhibit and pavilion also helped introduce Americans to Japanese culture, religion, arts, and architecture at a time (post-Meiji Restoration) when Japan was especially anxious to show the world its power, modernization, and accomplishments. Frank Lloyd Wright was but one of several architects and artists influenced by the Phoenix Pavilion, but the impact on him was arguably transformational leading not only to prairie houses but large structures such as the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, and it influenced his decorative arts. It’s not only the exterior look and visible (“unmasked”) structure with form following function, and combination of fine craftsmanship with simple, everyday materials, but also the interconnecting corridors and holistic flow of the “rooms” that influenced Wright and others.”

The Palace of Fine Arts for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition is now the Museum of Science and Industry.

(photo by Bill F. Eger)

It remains a place of tranquility between the University of Chicago to the west and the Lake Michigan shore to the east, a baseball field, marina and golf course to the south and the Museum of Science and Industry to the north. The Museum of Science and Industry is the last remaining structure on the site of the 1893 fair. Built as the Palace of Fine Arts, it was of more substantial, fire-proof construction to protect the art.

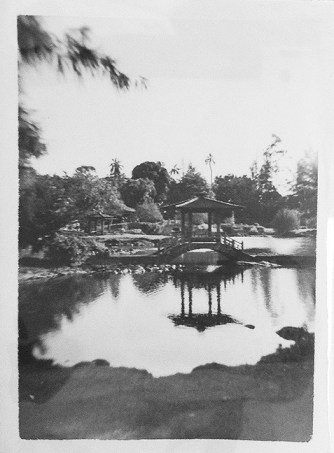

The Ho-o-den was donated by the Japanese government at the close of the 1893 fair with the intention that it remain as a lasting memento. In 1933, for the Century of Progress World’s Fair, Chicago and the government of Japan constructed a traditional tea house on Chicago’s near/mid-south lakefront and also created a garden on Wooded Island’s northeast side and refurbished the Ho-o-den. The garden was designed by issei Taro Otsuka, a garden builder based in the Midwest. After that fair closed, a torii gate, the Nippon Tea House and lanterns from the Century of Progress were moved to Wooded Island in 1935.

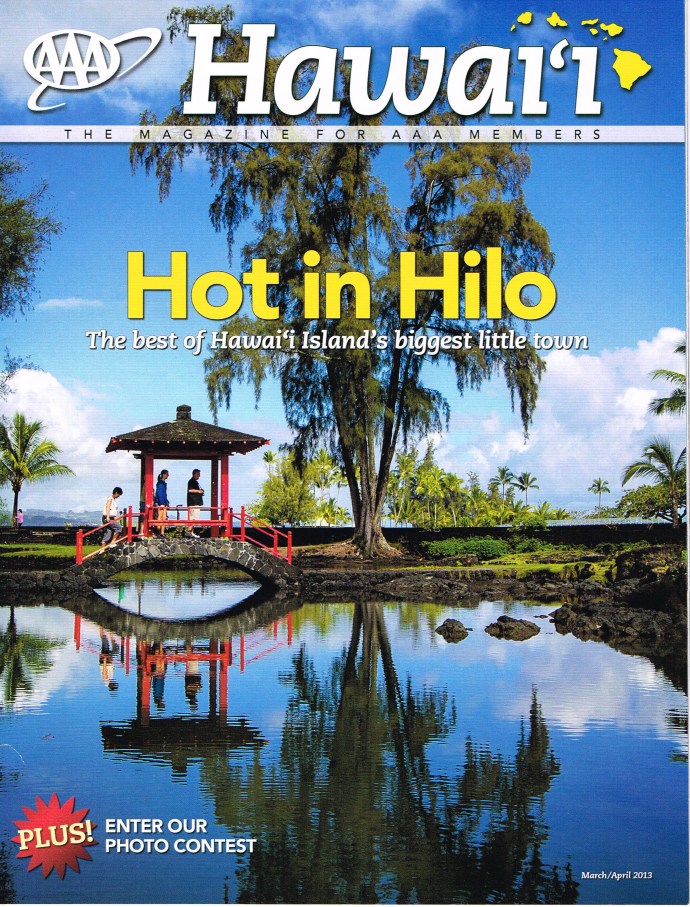

The Noh Stage style pavilion will serve as a gathering spot for cultural displays and presentations. It is located on the same spot as the 1933 tea house. The waterfall offers several points from which to view cascading water. A flat rock crossing below the waterfall offers an even closer view.

(photo by Bill F. Eger)

More work on the Japanese garden was done by George Shimoda and built with assistance from Japan. As it does today, the garden consisted of a double pond with islands, a cascading waterfall, stone walkway, flowering cherry trees, iris, lilies, a moon bridge, rock formations and stone lanterns.

The garden and buildings fell prey to public fears during World War II and several fires destroyed the buildings from 1941 to 1946. Gradually, the site became neglected and overgrown.

One rebirth began in 1973 with the formalizing of a Sister City relationship with Osaka, a relationship that went back to the 1950s. Also in 1973, Douglas C. Anderson began leading bird walks “in part to reclaim them for birders and the communities of Hyde Park, Woodlawn and South Shore. Gradually, thanks in good measure to Doug and to picnics/People in the Park events held by the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference and Open Lands, citizens and birders returned, rediscovered Osaka Garden and demanded its restoration,” Ossewaarde wrote.

“Also, by 1974 Jackson Park had been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. During that decade, the Park District added new landscaping, stabilized the shoreline and either restored or reconstructed most of the original features.”

Pine, bridge and stones — all carefully placed — are reflected in the surface of the pond below the waterfall (behind and to the right of this point of view).

Another rebirth occurred in the 1980s when designer Kaneji Domoto was brought in. He was known for his work designing Japanese gardens at the 1939 world fairs at both Treasure Island in California and in New York. Nissei Domoto (1913-2002) worked at his parents’ Northern California nursery and later was interned at the Granada War Relocation Center during WWII. He studied at Berkeley and with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin and had a 50+ year career as an architect and landscape designer. In 1974, he authored Bonasi and the Japanese garden. In 1983, Domoto received the Frederick Law Olmsted Award for his redesign of the Japanese garden at Jackson Park. George Cooley, formerly a JPAC officer and Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference officer, shepherded planning and secured grants including federal funds for the Garden restoration.

The designs of the 1970s and 1980s followed the original paths designed in 1893 to provide a stroll through the wooded area.

Text of the sign reads: “The Osaka Japanese Garden is a culturally authentic site, designed to create a feeling of peace and tranquility. Please stay on the paths and refrain from activities that will disrupt the special experience for other patrons. Your pets are welcome if they remain leashed and you pick up after them. Thank you for your cooperation.”

(photo by Bill F. Eger)

The next phase was in 1992 and 1993 when the 20th anniversary of the Sister City relationship was celebrated and the Garden was renamed Osaka Japanese Garden (1993). In 1994-95 a new traditional formal gate and fence, were dedicated, funded by the City of Osaka and constructed entirely without nails and by hand using tongue and groove methods. A major historical study and report were produced in 1992.

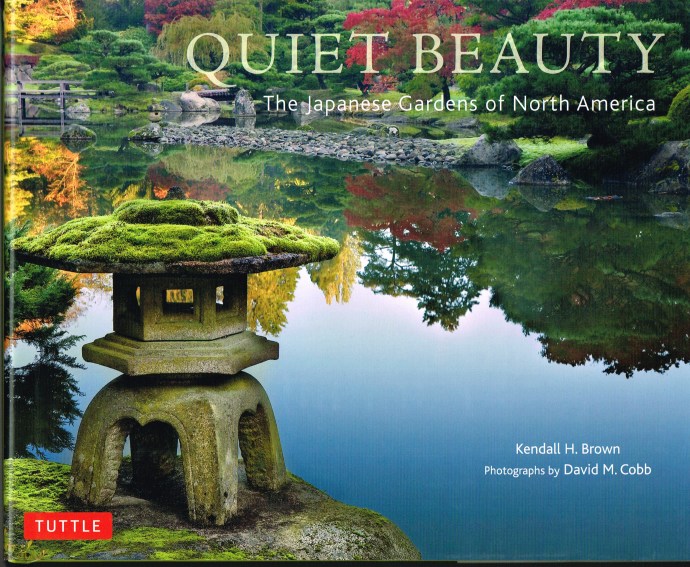

Yet another rebirth began in 2000 with the direction of Sadafumi Uchiyama in creating a master plan for the garden. Uchiyama is a third generation Japanese gardener from southern Japan, His family’s involvement in the business dates back to the Meiji era (1909). He served as secretary of the International Association of Japanese Gardens from 1996 to 2000 and currently is garden curator of the Portland Japanese Garden and a member of the board of directors of the North American Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA). Uchiyama received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in landscape architecture from the University of Illinois and is licensed in Oregon and California.

Initial work was completed in 2001 with steel retaining walls that line the banks of the pond, 100 tons of new boulders to shore up the edges of the pond and lagoon, and resetting of 120 tons of rock. Uchiyama picked jagged stones to redesign the “behavior of the water” in the waterfall. It flows into the pond at 600 gallons per minute.

Stone from Wisconsin was chosen to augment stone already in the garden.

“In 2008, after a hiatus in reestablishing a maintenance contract, and some less than satisfactory catch up pruning, parties including the City of Osaka Chicago Office, new contractors Clauss Brothers, expert pruning supervisor Bill Koons, CPD supervisor Karen Szyka and Department of Planning and Development took action. Main improvements included repair and cleaning of the torii gate, numerous cherries, replacement of a burr oak blown down in a storm, and most important replacement of the waterfall pump,” Ossewaarde wrote.

“Rededication on October 18, 2008 — the 35th anniversary of the Sister City partnership — included dedication by the Vice Mayor of Osaka and performances of a traditional sit down comedy–Kaishi and two Rakugo.”

This lantern may date back to the 1893 fair.

(photo by Bill F. Eger)

“Everyone is aware that some shoring up will still be needed, and such gardens need permanent funding to make the intensive maintenance sustainable– and high level of security. Any permanent oversight group will have to look at which garden template is to be the goal, bearing in mind that a Japanese garden is meant to be changing and evanescent through the seasons and years– a never-ending work of art.

“The Garden’s theme, from 1893 to the present, is peace–between humans and nature, within people, with the spiritual realm, and between peoples. These themes are dear to the people of Osaka, Chicago, and the park’s neighboring communities. Long may this garden continue. As the Osaka Garden Committee of Sister Cities International wrote, ‘A garden develops over time….it is lasting. The same is true of the relationships between people, nations and cultures. Every gardener knows that quiet observation and attention to nature facilitate the success of a garden. Likewise, peace and understanding facilitate our future’.”

A waterproof box under a sign pointing the way to the entry bridge holds a history of Wooded Island and a guide to trees planted along the entire island’s paths.

On a personal note: This area of Chicago holds many memories for both my husband and me. Bill attended the University of Chicago in the mid-1950s. For me as a youngster living in Michigan, a trip to the Museum of Science and Industry was a really big deal. On this trip we spent the afternoon at the Museum until closing then were met by Osaka Garden docent Sonia Cooke.

It was a true delight to be in her presence wandering from the museum to the bridge leading to the garden and all through every part of this lovely jewel. Her lifetime knowledge of architecture and her current enthusiasm for the garden made our visit most enjoyable. Thank you Sonia. And thank you Robert Karr and William Florida of the Friends of the Japanese Garden for putting us together.

Thank you Gary Ossewaarde for permission to quote from your extensive history. For those who wish more information, please look at http://www.hydepark.org/parks/osaka2.htm#history

On the list for repair is this traditional arched bridge.

(photo by Bill F. Eger)

Photos not otherwise credited in this blog are by K.T. Cannon-Eger. To see a full size image, click on any photo. Comments on this and other articles are welcome.

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893

from Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography by Meryle Secrest, published by The University of Chicago Press in 1992, pages 185-187

“Most writers agree that Wright’s interest in Japanese art probably began with the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, if not before — one recalls that, as a member of [Louis] Sullivan’s office, he would have had detailed knowledge of the advance planning — and, in particular, with one of the most popular exhibits, “The Ho-o-den,” a wooden temple of the Fujiwara Period, which the Japanese government erected on a small plot of ground set in an artificial lake. It was the first real introduction of Japanese art and architecture to the Middle West. In terms of the enormous interest in all things Japanese that had followed Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s trip to Japan in 1845, this discovery must be considered rather late. Bronzes, lacquers, fans, ceramics, and above all, prints had been flooding to Europe for twenty or thirty years, and artists as disparate as Redon and Steinlen had drawn new inspiration from these exotic and unfamiliar objects, seizing on the lessons they had to teach as a way to revitalize their imagery.

“Architects were just as susceptible and, after the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, where Japanese pavilions had been built, and especially after publication of the first English-language book on Japanese architecture in 1886, they focused their attention on this aspect of Japanese culture. For Americans oriented toward the Arts and Crafts Movement, Japan offered ‘the example of an indigenous culture that embodied the organic quality they found in the middle ages,’ as Richard Guy Wilson wrote. He added, ‘Japanese motifs from curved gable ends to nearly wholesale replication of pagodas and torii gates, appeared in Arts and Crafts houses and bungalows from coast to coast.’ One believes Wright’s new interest to have been at least partly connected with the exhaustion White had noticed and remarked upon just before his employer left for Japan [in 1905]. It began the year before, White wrote, when Wright seemed very ‘petered out.’ However, in the last three months it had been impossible to get Wright to give his office any attention at all. In fact, Wright had been confined to bed for several weeks that winter with a case of tonsillitis that had made its way around the family. He returned from Japan in May sounding more like his old self. … His interest was entirely genuine and his visit would have a lasting influence.

“Several writers claim to see a more or less direct connection between the Japanese temple that Wright saw at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and some of his own buildings. Vincent Scully demonstrated that the treatment of exteriors in the Willits house resembled those of the Ho-o-den, and Wright’s use of light-colored stucco panels edged with bands of darker wood seemed to suggest Japanese models as well. Scully published copies of the two floor plans to support his assertion that the house Wright designed for Willits was modeled almost exactly on that of the Japanese shrine. Another authority on Wright believed he had been most influenced by the Japanese print, and he had certainly begun to collect ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) sometime before his first visit to Japan, because photographs of his interiors showed such prints prominently displayed. He returned from Japan with over two hundred woodcuts by Hiroshige, considered the artist to have had the greatest influence on the West, and lent them to the Art Institute of Chicago a year later for the first ukiyo-e exhibition to be held in that museum. He bought them as investments, making no bones about being a dealer, and was so successful that he had a sizable collection of Japanese prints on hand all his life, to be cashed in when necessary, and some famous collectors as clients. But he was also passionately interested in the subject, almost obsessed, and would talk endlessly about the exquisite qualities of these prints, their serenity, simplicity, sense of the natural world and reduction to essentials. While on that first trip he wore native robes and took extended trips into the interior to collect his prints and porcelains. All of this indicates that the feelings aroused by Japanese art were wholehearted, yet there is a suggestion that, at some level, Wright was made acutely uncomfortable by that most conformist, ordered and rigidly circumscribed culture that he apparently admired for its spirituality.”

Wright returned to Japan for many months during the years 1916 to 1922 building not only the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo but also residences such as that for Aisaku Hayashi in 1917.